CyberBunker was a “bulletproof” hosting operation run primarily by Xennt or Herman-Johan Xennt, and CB3ROB or Sven Kamphuis (specifically early on).

It opened up in the late 1990s operating out of a real decommissioned NATO bunker in Kloetinge, Netherlands.

It became somewhat of a success, primarily hosting pornographic content.

Sometime in 2002, however, a fire broke out in the bunker from another tenant Xennt rented to that were using the bunker as an MDMA lab. Quite a few people went to prison over it, but no one from CyberBunker.

The incident led to CyberBunker essentially being kicked out of Kloetinge, and moving to other various locations, including Amsterdam. Another company named BunkerInfra even purchased the bunker back in 2010, and later stated all of the CyberBunker materials were photoshopped.

From this point forward, the same group of individuals kept the same name — but no longer operated out of the original NATO bunker.

What’s Real and What’s Fake?

A lot of the information surrounding CyberBunker seems to have been deliberately faked to stir up attention around the brand.

There’s a lot of misleading information out there surrounding CyberBunker and a lot of that is from CyberBunker themselves.

Using archive.org I was able to go back and look at their comically early 2000s website.

One page titled: “SWAT TEAM RAIDS BUNKER” particularly caught my attention…

On the page, they went on to say:

Before the break of dawn on a morning in April, a full SWAT team was sent to execute a search warrant on CyberBunker’s property. Most of the staff inside were still asleep, while others were watching a movie. Surveillance cameras covering the fenced-in area of the property recorded the entire event. It is apparent in the video that armed SWAT police, wearing black bulletproof vests and white helmets, forced entry to the property by cutting through the outer fence of the property. Once they gained entry, they began to quietly approach the bunker. Also on scene was a reporter to cover the event.

Once the SWAT team reached the bunker’s blast doors, they ‘knock’ to announce their presence. It is unclear exactly what they say, as no sound is recorded from the surveillance system. CyberBunker is equipped with an advanced Intruder Detection System (IDS), however due to a testing drill the previous night the IDS system was accidentally left in the inactive mode. Two SWAT officers are seen to hit the blast door of the bunker with a battering ram. It must not have occurred to the officers that the blast doors were designed to withstand a 20 megaton nuclear explosion from close range. When the SWAT team realized that the door was not being opened for them, they throw flashbangs and take other actions to draw attention. The surveillance footage shows quite a lot of activity at this point. On the other side of the blast doors, no one inside the bunker noticed anything unusual. The SWAT team did some further investigating, and appears to be making phone calls. Finally the SWAT team realized what occurred when City Hall attempted to breach the blast doors. Apparently recognizing that they had gone overboard on their raid, the SWAT team decided to go home.

Later that afternoon, CyberBunker’s security was wide-awake to discover that the motion detection system had been tripped. They were in fact astounded to learn what had taken place by replaying the footage. In an attempt to learn exactly what happened, CyberBunker’s general manager Jordan Robson, decided to call the police. Unfortunately, the police department claimed that they were not aware of the raid. They insisted that no SWAT team had been sent to the property.

CyberBunker’s lawyers later discovered that the police had indeed sent officers to the bunker for what they claimed was a “routine check” and that nothing out of the ordinary had taken place. When CyberBunker’s lawyers suggested that the surveillance footage could be put online, the police department then quickly offered to pay to repair the damage caused to the fence.

After paying € 8088.- euros to CyberBunker, nothing further was heard from the SWAT team. The search was most likely another futile attempt to find something illegal. None of CyberBunker’s security or staff have a clue as to what the raid might have been about.

I’m not convinced at all this ever occurred. Furthermore, those police officers don’t even look real.

So you have weird things like this, that are probably fake, and then you have the company photoshopping their logo onto the bunker that caught on fire in the past from an MDMA lab.

In fact, between the time the original bunker caught on fire and when they replaced it with a new bunker, I think for about 10 years of their business (in their prime, really) they were entirely operating under false premises of being physically located in a bunker as a selling point.

Oh, and I have to show you this other screenshot from their site, too…

Yes, I too frequently relate bulletproof Netherlands hosting along with golfing and Audi R8s.

But, let me not confuse you… CyberBunker was a real hosting operation, just a bit exaggerated.

They did have quite a few real clients, and here shortly, you’ll see the police taking notice of CyberBunker is very real, too.

All Roads Lead to Spamhaus

CyberBunker was profitable between the early 200s to the early 2010s. Even with clients like Pirate Bay and WikiLeaks, it kept growing and mostly stayed out of any serious trouble.

For bulletproof hosts, often growth is what causes death. They only exist by being unnoticed.

The success of CyberBunker led to Spamhaus taking notice. In March 2013, Spamhaus blacklisted CyberBunker.

Following that, a massive distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack, unprecedented in scale, targeted Spamhaus.

That attack, which peaked at 300 Gbit/s, persisted for over a week and prompted an investigation by multiple global cyber-police forces. While Spamhaus accused CyberBunker and various Eastern European and Russian “criminal gangs” of orchestrating the attack, CyberBunker remained silent.

After being in contact with both Xennt and Kampuis, the New Yorker stated the following about the situation:

In the two-thousands and twenty-tens, CyberBunker and Kamphuis’s associated Internet-service provider, which was also called CB3ROB, had become notorious for hosting the spam e-mail operations of phishing sites—fraudulent criminal enterprises that lure people into disclosing their credit-card details—and of rogue pharmaceutical peddlers. At the same time, CyberBunker hosted WikiLeaks, the renegade operation devoted to exposing secret documents. (Xennt told me that this was not a political gesture on his part: “CyberBunker hosted WikiLeaks indeed. Why? Because WikiLeaks hired its services.”) The Pirate Bay, a site for sharing movies and other copyrighted content, was a CyberBunker client until 2010, when the Motion Picture Association of America won a court ruling, in Hamburg, that forced Xennt and Kamphuis to remove the site from its servers. Kamphuis was indignant about the decision, telling a reporter, “Help us put these dinosaurs out of their misery!”

As Angerer continued to research CyberBunker, he learned that it could be very aggressive. Around 2010, the Spamhaus Project, a European volunteer-driven organization whose goal is to impede spammers, had begun listing I.P. and real addresses associated with CyberBunker and CB3ROB, and had lobbied Internet-service providers to block the company. In early 2013, this pressure led to CB3ROB’s services being briefly taken off-line. In retaliation, Kamphuis and a loose group of hackers in different countries, who called themselves the Stophaus Collective, hit Spamhaus with a distributed denial-of-service attack, which incapacitates a site by overloading it with traffic. Kamphuis was arrested shortly after the attack, but Xennt was not; he proceeded with moving into the Traben-Trarbach bunker.

Sven Olaf Kamphuis was later arrested near Barcelona on 25 April 2013 at the request of Dutch authorities, with collaboration from Eurojust.

Later, he was extradited to the Netherlands, found guilty in connection with the Spamhaus attack, and received a suspended 240-day prison sentence, credited for the 55 days he had already spent in custody.

That brings us to the new bunker…

CyberBunker Moves to Germany

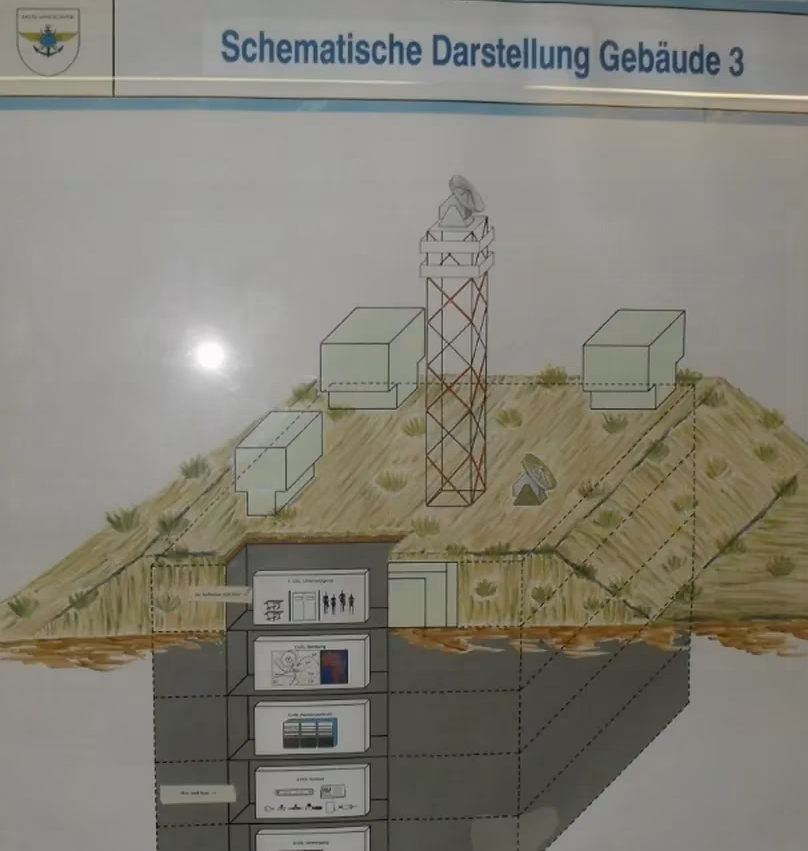

2013 was an eventful year for CyberBunker. It was also the same year they decided to make a new move to Germany and purchase its second bunker in Traben-Trarbach, Germany.

In 2014 however, back home in the Netherlands, a CyberBunker server was seized in Amsterdam (colocated at Leaseweb) that was responsible for hosting a famous darknet market, Cannabis Road — this is what in my opinion flagged Xennt, and led to the death of CyberBunker.

By 2015, the German government was already investigating CyberBunker, specifically Xennt. As early as 2015, Germany was officially intercepting the bunker’s traffic.

Simultaneously, the United States, Germany, and the Netherlands were all working together, building cases against other dark net markets, specifically Wall Street Market, which at that time was being actively hosted at CyberBunker.

In April 2019, the United States government ended up being the first to make arrests, arresting the suspected operators of Wall Street Market, and seizing the servers from CyberBunker in Germany.

There was even a thread opened up over on LowEndTalk about it way back in 2019.

This was the domino that led to the downfall of CyberBunker, by September 2019, Xennt was arrested by German authorities and the new German CyberBunker was officially raided.

Hundreds of drives were seized, and the compound was ultimately shut down.

All Good Things Must Come to an End

Sven Kamphuis was never arrested and was never listed as a suspect, but he did publicly go out against the police seizure and arrest.

Xennt stated Kamphuis wasn’t involved in the German bunker. The police stated Kamphuis had a decreasing level of involvement after 2014.

It seems regardless if Kamphuis was involved with the German version of CyberBunker or not, he got off free — besides his 2-month stint in jail.

Xennt’s trial lasted longer than a year and as of December 2021, resulted in Xennt being sentenced to almost 6 years in prison, with the other suspects being arrested (including Xennt’s own children) receiving anywhere between suspended sentences to four years.

I guess all good things must come to an end after all.

R.I.P. CyberBunker

More renegade web host stories.

Less YouTube and homosexual advertising.

eyyyy are you homophobic, racist? are you against liberty, freedom and rights?

I’m gayyyyy I support technology and sciencee

It’s because of gayyyy pride that science have advanced sooo much, Oh my Bf is calling me cyaaa

we make times haaaard u know, we so beautiful it even make time hard, and then,,,,,, and then! strong man appear, omg look at him soo chad