Phil Zimmermann created Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) way back in 1991. At one point in 1993, PGP was considered by the United States government as a “non-exportable weapon” with Zimmermann having an actual criminal investigation opened into him.

(Phil Zimmermann, creator of PGP, is pictured above.)

Basically, the reason Phil Zimmermann didn’t become a political pawn sentenced to prison is because MIT open-sourced the PGP code:

MIT came to Zimmermann’s defense by publishing a 600-page book that included the PGP code, which meant that if Phil Zimmermann was an illegal arms dealer, then so was one of America’s most prestigious universities. The newly formed Electronic Frontier Foundation took on the case of another embattled cryptographer, leading to a landmark 1995 decision that declared that software code was a form of speech, and thus protected under the first amendment. In 1996, the feds announced that they were no longer pursuing a criminal indictment for the international release of PGP. After a strange, unwanted interlude as a rogue arms dealer, Phil Zimmermann went back to being what he had been all along: a programmer and civil liberties activist.

Nowadays it’s primarily used for signing and encrypting various forms of communication, such as email.

Most 30-year-old projects fall off sometime during that timespan; not PGP. PGP is more relevant than ever before with many email providers relying on the standard for encryption. For example: the most popular privacy-centric email provider, ProtonMail, uses PGP for its encryption.

How Does PGP Encryption Work?

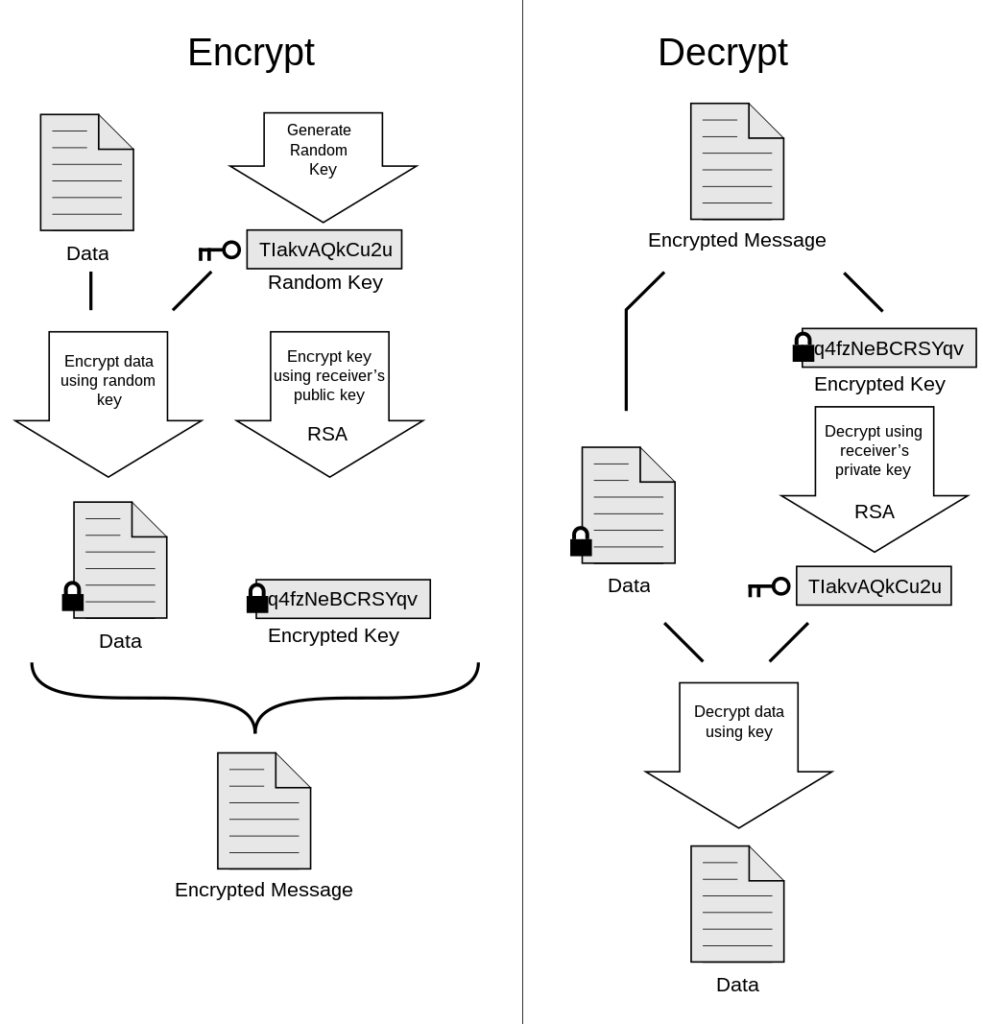

Let me break down for you how PGP works:

- Person A wants to communicate with Person B securely.

- Person A creates private and public PGP key.

- Person A shares their public key with Person B.

- Person B encrypts a message using Person A’s public key (signing with their own private key).

- Person B sends back an encrypted message that can only be read by decrypting the message, using Person A’s private key.

- Person A can now decrypt the message and communicate securely and successfully.

Here’s a graphical breakdown from Wikipedia:

In simple terms, it provides end-to-end encryption with no possibility of a snooping middleman.

Technically Broadcom Owns PGP

Originally the rights to the PGP encryption software belonged to PGP Inc back in 1991. Since then, the company has changed significantly.

Most recently it was bought by Symantec, but then Symantec was bought by Broadcom, INC. As of right now… Broadcom owns PGP.

However, GnuPG is a very popular alternative that utilizes the OpenPGP standard and is entirely free for use, forever. These formats are identical.

Here’s how GnuPG describes itself:

GnuPG is a complete and free implementation of the OpenPGP standard as defined by RFC4880 (also known as PGP). GnuPG allows you to encrypt and sign your data and communications; it features a versatile key management system, along with access modules for all kinds of public key directories. GnuPG, also known as GPG, is a command line tool with features for easy integration with other applications. A wealth of frontend applications and libraries are available. GnuPG also provides support for S/MIME and Secure Shell (ssh).

Since its introduction in 1997, GnuPG is Free Software (meaning that it respects your freedom). It can be freely used, modified and distributed under the terms of the GNU General Public License .

How To Create PGP Encrypted Messages

Creating PGP-encrypted messages, texts, and emails is easier than you’d think. GnuPG has an easy-to-use client for practically any OS or distro.

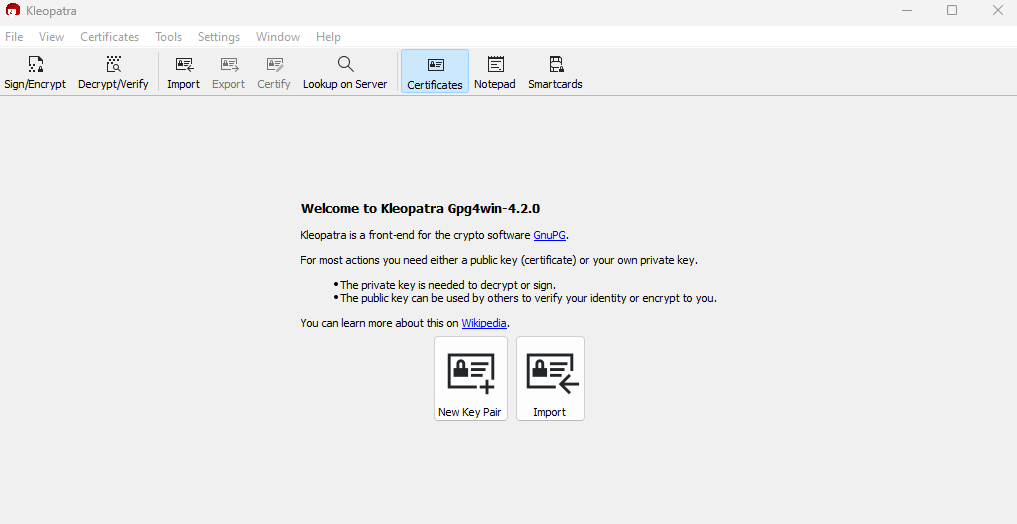

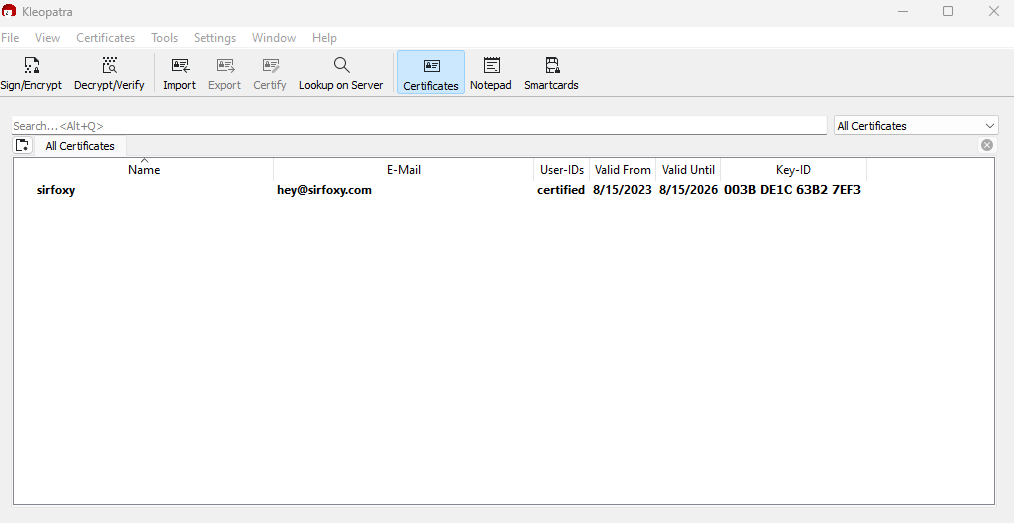

On Windows (my main OS), they call it Gpg4win:

All you have to do is download it using the link above, install it, and run it. Then you’ll be presented with the following screen:

Click “New Key Pair”, and fill out your desired name and email associated with it.

I strongly suggest you click to protect the generated key with a passphrase. It may take a bit to generate the key, depending on your device.

You’ll then see your generated key:

My public key, for instance, looks like this:

-----BEGIN PGP PUBLIC KEY BLOCK-----

Comment: User-ID: sirfoxy <hey@sirfoxy.com>

mDMEZNvH/hYJKwYBBAHaRw8BAQdA5YteukOJVCxoVCwExnd/QkQL3lartpS2HZnG

o70PsVG0GXNpcmZveHkgPGhleUBzaXJmb3h5LmNvbT6ImQQTFgoAQRYhBFA9/Ovv

59srD6B6bgA73hxjsn7zBQJk28f+AhsDBQkFpNMSBQsJCAcCAiICBhUKCQgLAgQW

AgMBAh4HAheAAAoJEAA73hxjsn7zBo8A/3zrfLrOciQV8ejsMgjsZ0eeZeUbIUNv

K8Wk79VW7aX/APwNzbWRG7uRnsko74uOjMAqBf0cG8CmWCi6V+WaceKVCbg4BGTb

x/4SCisGAQQBl1UBBQEBB0ADxsrbA9dIrtKliKQ4oM2AdWUTgmBEkvR7OPNHzSvy

RwMBCAeIfgQYFgoAJhYhBFA9/Ovv59srD6B6bgA73hxjsn7zBQJk28f+AhsMBQkF

pNMSAAoJEAA73hxjsn7zE1oA/1PBhk3ZXu0rZuND7b5c8zVddQSNOJ9fZM3vjkTQ

VO4XAP9+H5WSbY9SFCIvJYqDetIZlwH7i0a985wnb3F2J9ULAA==

=mggY

-----END PGP PUBLIC KEY BLOCK-----

Now anyone could use that public key to encrypt their communications with me.

All you would have to do to create your own PGP encrypted conversation with me for instance would be to import that public key, write your message, and then sign that message with your private key (all possible through Gpg4win or alternatives).

You could then send me that message through any platform, such as email, social media, LowEndTalk, or beyond and nobody would be able to understand a thing.

It’d be entirely encrypted until I decrypt it with my private key. It’s end-to-end encryption, so the middleman only sees gibberish.

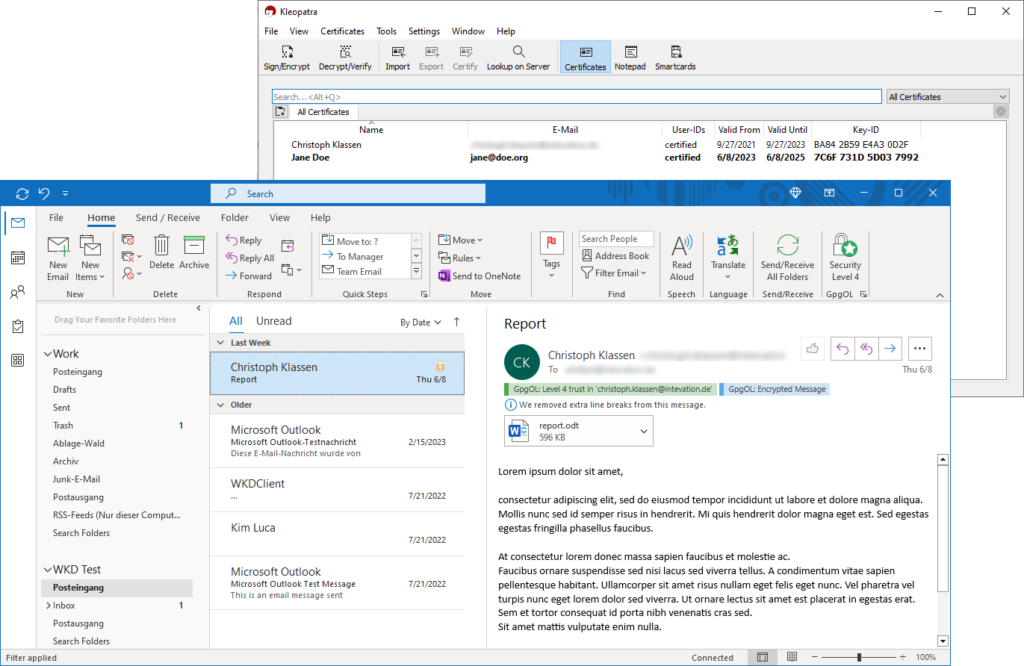

It’s that simple, and there are further integrations you can do with your favorite clients to automatically encrypt your communications.

PGP Encryption Brings Privacy Back Into Your Own Hands

In an era of increasingly higher levels of skepticism around privacy… it’s never a bad thing to bring the power of privacy back into your hands.

That’s specifically why Philip Zimmermann wrote PGP, after all:

It’s personal. It’s private. And it’s no one’s business but yours. You may be planning a political campaign, discussing your taxes, or having an illicit affair. Or you may be communicating with a political dissident in a repressive country. Whatever it is, you don’t want your private electronic mail (email) or confidential documents read by anyone else. There’s nothing wrong with asserting your privacy. Privacy is as apple-pie as the Constitution.

The right to privacy is spread implicitly throughout the Bill of Rights. But when the United States Constitution was framed, the Founding Fathers saw no need to explicitly spell out the right to a private conversation. That would have been silly. Two hundred years ago, all conversations were private. If someone else was within earshot, you could just go out behind the barn and have your conversation there. No one could listen in without your knowledge. The right to a private conversation was a natural right, not just in a philosophical sense, but in a law-of-physics sense, given the technology of the time.

But with the coming of the information age, starting with the invention of the telephone, all that has changed. Now most of our conversations are conducted electronically. This allows our most intimate conversations to be exposed without our knowledge. Cellular phone calls may be monitored by anyone with a radio. Electronic mail, sent across the Internet, is no more secure than cellular phone calls. Email is rapidly replacing postal mail, becoming the norm for everyone, not the novelty it was in the past.

Until recently, if the government wanted to violate the privacy of ordinary citizens, they had to expend a certain amount of expense and labor to intercept and steam open and read paper mail. Or they had to listen to and possibly transcribe spoken telephone conversation, at least before automatic voice recognition technology became available. This kind of labor-intensive monitoring was not practical on a large scale. It was only done in important cases when it seemed worthwhile. This is like catching one fish at a time, with a hook and line. Today, email can be routinely and automatically scanned for interesting keywords, on a vast scale, without detection. This is like driftnet fishing. And exponential growth in computer power is making the same thing possible with voice traffic.

Perhaps you think your email is legitimate enough that encryption is unwarranted. If you really are a law-abiding citizen with nothing to hide, then why don’t you always send your paper mail on postcards? Why not submit to drug testing on demand? Why require a warrant for police searches of your house? Are you trying to hide something? If you hide your mail inside envelopes, does that mean you must be a subversive or a drug dealer, or maybe a paranoid nut? Do law-abiding citizens have any need to encrypt their email?

What if everyone believed that law-abiding citizens should use postcards for their mail? If a nonconformist tried to assert his privacy by using an envelope for his mail, it would draw suspicion. Perhaps the authorities would open his mail to see what he’s hiding. Fortunately, we don’t live in that kind of world, because everyone protects most of their mail with envelopes. So no one draws suspicion by asserting their privacy with an envelope. There’s safety in numbers. Analogously, it would be nice if everyone routinely used encryption for all their email, innocent or not, so that no one drew suspicion by asserting their email privacy with encryption. Think of it as a form of solidarity.

Senate Bill 266, a 1991 omnibus anticrime bill, had an unsettling measure buried in it. If this non-binding resolution had become real law, it would have forced manufacturers of secure communications equipment to insert special “trap doors” in their products, so that the government could read anyone’s encrypted messages. It reads, “It is the sense of Congress that providers of electronic communications services and manufacturers of electronic communications service equipment shall ensure that communications systems permit the government to obtain the plain text contents of voice, data, and other communications when appropriately authorized by law.” It was this bill that led me to publish PGP electronically for free that year, shortly before the measure was defeated after vigorous protest by civil libertarians and industry groups.

The 1994 Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) mandated that phone companies install remote wiretapping ports into their central office digital switches, creating a new technology infrastructure for “point-and-click” wiretapping, so that federal agents no longer have to go out and attach alligator clips to phone lines. Now they will be able to sit in their headquarters in Washington and listen in on your phone calls. Of course, the law still requires a court order for a wiretap. But while technology infrastructures can persist for generations, laws and policies can change overnight. Once a communications infrastructure optimized for surveillance becomes entrenched, a shift in political conditions may lead to abuse of this new-found power. Political conditions may shift with the election of a new government, or perhaps more abruptly from the bombing of a federal building.

A year after the CALEA passed, the FBI disclosed plans to require the phone companies to build into their infrastructure the capacity to simultaneously wiretap 1 percent of all phone calls in all major U.S. cities. This would represent more than a thousandfold increase over previous levels in the number of phones that could be wiretapped. In previous years, there were only about a thousand court-ordered wiretaps in the United States per year, at the federal, state, and local levels combined. It’s hard to see how the government could even employ enough judges to sign enough wiretap orders to wiretap 1 percent of all our phone calls, much less hire enough federal agents to sit and listen to all that traffic in real time. The only plausible way of processing that amount of traffic is a massive Orwellian application of automated voice recognition technology to sift through it all, searching for interesting keywords or searching for a particular speaker’s voice. If the government doesn’t find the target in the first 1 percent sample, the wiretaps can be shifted over to a different 1 percent until the target is found, or until everyone’s phone line has been checked for subversive traffic. The FBI said they need this capacity to plan for the future. This plan sparked such outrage that it was defeated in Congress. But the mere fact that the FBI even asked for these broad powers is revealing of their agenda.

Advances in technology will not permit the maintenance of the status quo, as far as privacy is concerned. The status quo is unstable. If we do nothing, new technologies will give the government new automatic surveillance capabilities that Stalin could never have dreamed of. The only way to hold the line on privacy in the information age is strong cryptography.

You don’t have to distrust the government to want to use cryptography. Your business can be wiretapped by business rivals, organized crime, or foreign governments. Several foreign governments, for example, admit to using their signals intelligence against companies from other countries to give their own corporations a competitive edge. Ironically, the United States government’s restrictions on cryptography in the 1990’s have weakened U.S. corporate defenses against foreign intelligence and organized crime.

The government knows what a pivotal role cryptography is destined to play in the power relationship with its people. In April 1993, the Clinton administration unveiled a bold new encryption policy initiative, which had been under development at the National Security Agency (NSA) since the start of the Bush administration. The centerpiece of this initiative was a government-built encryption device, called the Clipper chip, containing a new classified NSA encryption algorithm. The government tried to encourage private industry to design it into all their secure communication products, such as secure phones, secure faxes, and so on. AT&T put Clipper into its secure voice products. The catch: At the time of manufacture, each Clipper chip is loaded with its own unique key, and the government gets to keep a copy, placed in escrow. Not to worry, though–the government promises that they will use these keys to read your traffic only “when duly authorized by law.” Of course, to make Clipper completely effective, the next logical step would be to outlaw other forms of cryptography.

The government initially claimed that using Clipper would be voluntary, that no one would be forced to use it instead of other types of cryptography. But the public reaction against the Clipper chip was strong, stronger than the government anticipated. The computer industry monolithically proclaimed its opposition to using Clipper. FBI director Louis Freeh responded to a question in a press conference in 1994 by saying that if Clipper failed to gain public support, and FBI wiretaps were shut out by non-government-controlled cryptography, his office would have no choice but to seek legislative relief. Later, in the aftermath of the Oklahoma City tragedy, Mr. Freeh testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee that public availability of strong cryptography must be curtailed by the government (although no one had suggested that cryptography was used by the bombers).

The government has a track record that does not inspire confidence that they will never abuse our civil liberties. The FBI’s COINTELPRO program targeted groups that opposed government policies. They spied on the antiwar movement and the civil rights movement. They wiretapped the phone of Martin Luther King. Nixon had his enemies list. Then there was the Watergate mess. More recently, Congress has either attempted to or succeeded in passing laws curtailing our civil liberties on the Internet. Some elements of the Clinton White House collected confidential FBI files on Republican civil servants, conceivably for political exploitation. And some overzealous prosecutors have shown a willingness to go to the ends of the Earth in pursuit of exposing sexual indiscretions of political enemies. At no time in the past century has public distrust of the government been so broadly distributed across the political spectrum, as it is today.

Throughout the 1990s, I figured that if we want to resist this unsettling trend in the government to outlaw cryptography, one measure we can apply is to use cryptography as much as we can now while it’s still legal. When use of strong cryptography becomes popular, it’s harder for the government to criminalize it. Therefore, using PGP is good for preserving democracy. If privacy is outlawed, only outlaws will have privacy.

It appears that the deployment of PGP must have worked, along with years of steady public outcry and industry pressure to relax the export controls. In the closing months of 1999, the Clinton administration announced a radical shift in export policy for crypto technology. They essentially threw out the whole export control regime. Now, we are finally able to export strong cryptography, with no upper limits on strength. It has been a long struggle, but we have finally won, at least on the export control front in the US. Now we must continue our efforts to deploy strong crypto, to blunt the effects increasing surveillance efforts on the Internet by various governments. And we still need to entrench our right to use it domestically over the objections of the FBI.

PGP empowers people to take their privacy into their own hands. There has been a growing social need for it. That’s why I wrote it.

The encryption is quite secure, about 5-6 years ago, I implemented it in secured chat application, but quite often use it, when I exchange sensitive encryption emails with my business contacts.

I’m a big fan of PGP. I have been right back to ’92 or thereabouts. It’s a shame but there are a few reasons why it has never achieved widespread popularity.

1. It’s can be massively complicated for a basic computer user to understand. Applications like Kleopatra go a *VERY* long way to easing the pain but there’s still pain there.

2. It introduces a secondary step that most people won’t tolerate.

3. It’s very easy to lose a secret key (HDD loss, forgotten passphrase, etc)

4. The ‘web of trust’ principal never reached critical mass to where it was useful or even started creating a ‘web’

5. Keyservers do not appear to be maintained and appear quite slow (using pgp.mit.edu is like wading through treacle)

I still use PGP, when exchanging sensitive information with equally security conscious people such as penetration testers and HMG. Sadly, even on those occasions I’m seeing newly minted keys being used.

/me just adds a link to their key on MIT to their email signature.