If you were going to make up a sensational story and you want people to believe it, the trick is to ground it in as much reality as you can. Feed in a lot of details that make sense or are at least plausible to someone who perhaps is unfamiliar with what you’re discussing.

If you were going to make up a sensational story and you want people to believe it, the trick is to ground it in as much reality as you can. Feed in a lot of details that make sense or are at least plausible to someone who perhaps is unfamiliar with what you’re discussing.

For example, most people either remember or have heard about the Y2K scare. And some may know that there is a Y2038 issue, when Unix’s 32-bit time (number seconds since midnight, January 1, 1970) rolls over. Y2038 is nearly a thing of the past now that systems use a 64-bit time_t, but people have heard of it and in the era we’re about to discuss, it was the hot “second story” of time crises. We were feverishly working to avert Y2K, and engineers would talk about Y2038 at lunch as the next headache.

So lets’s take that real-world issue and wrap it around a piece of hardware that is real but almost no one has heard of, and salt in a little doctored photos and a bit of science fiction and…yeah, I think we’re starting to spin up something interesting.

And that’s just what someone did in the early days of the Internet. One of the most magnetic legends of that era was about a time traveler coming back in time to retrieve a computer, and save the world from the Y2038 issue.

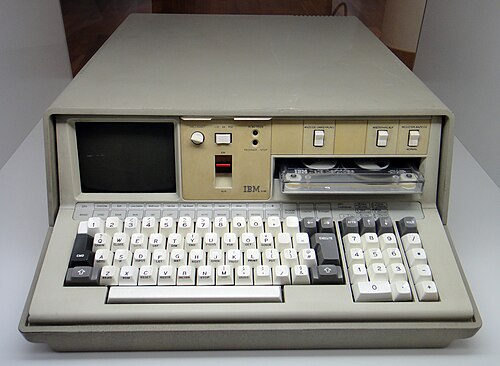

Not a sleek laptop. Not a quantum widget. A real, historical machine: the IBM 5100 – an almost comically heavy “portable” computer from the 1970s. A box that looks like something you’d rescue from a flood with two friends and a handcart.

And yet, that absurd detail is exactly what made the story stick.

Because the best hoaxes don’t start by demanding belief. They start by sounding just plausible enough to argue about.

This is the story of John Titor

Time Travelers

There are various “time traveler” photos you can find on the web. There’s a guy who was photographed wearing wraparound glasses and a logo T-shirt and holding a small portable camera in 1941. Impossible! Must be from the future! But actually, all those items existed at that time.

Or the woman in this 1938 video who appears to be talking on a cell phone. In reality, it’s either a portable radio or a small hearing aid device.

There’s the famous Rudolph Fentz tale: a man in old-fashioned clothes appears in Times Square with antique money and items, gets hit by a car, and is “discovered” to have vanished decades earlier. It reads like a perfect police-file urban legend – until researchers trace it back to fiction that later got repeated as fact.

Then there’s the Andrew Carlssin story: a supposed time traveler arrested for impossibly successful stock trades, who claims he came from the future. The details are deliciously specific – just enough numbers and law-enforcement flavor to feel real – until you learn it originated in the Weekly World News.

These stories are snapshots. One flare, one rumor, one punchline.

John Titor wasn’t a snapshot.

He was a thread.

The Early Internet

The internet of the late ’90s and early 2000s didn’t feel like today.

There were fewer platforms, fewer feeds, fewer recommendation engines shoving content into your face. If something spread, it often did so because people copied it by hand into forums, emails, personal websites, and archived pages that looked like they were coded at 2 a.m. with sheer willpower.

It wasn’t “viral.” It was communal.

I genuinely miss it, to be honest. You had yahoos just like today, but it seemed like humanity was forming this organic ball of thread where people were connecting, communities were forming, and everything was done by hobbyists. Maybe that’s why I like privately run forums (like LowEndTalk) instead of social media. It was a simpler time.

That environment created a perfect incubator for a new kind of legend: one that wasn’t blasted over social media to billions, but rather dropped in targeted communities where attentive, eager ears lapped it up.

That’s where John Titor arrived.

First Contact: a Fax to Late-Night Radio

Before the forums, the story begins the way a lot of pre-social-media lore begins: late-night radio.

In 1998, Art Bell, host of Coast to Coast AM, received a fax from someone claiming to be from the future. On air, Bell read what sounded like a strange mix of warning, technical explanation, and sci‑fi premise: time travel invented decades ahead, timelines branching, the future scarred by catastrophe.

It’s hard to overstate what Coast to Coast was in that era: a nightly campfire for callers with wild stories, and listeners who wanted to believe (or at least wanted to listen hard enough to decide).

So the story got an immediate visibility boost at the start.

And then, two years later, the story didn’t fade. It migrated.

2000: A Username Appears

In November 2000, on an online forum dedicated to time travel discussion (Time Travel Institute), a user appeared: TimeTravel_0. John Titor (his name) posted about his time travel mission, and hung around answering questions in a steady, matter-of-fact tone. He was the guy who’d faxed Art Bell.

He wasn’t selling anything, and didn’t seem to care if you believed him or not. He had an authenticity to him, like he really was from the future and was just killing time while his mission in our time played out. You imagined that if you went back to, say, 1930, you’d probably want to chat with the people there, and that’s what John was doing.

He had stopped in 2000 not only for his mission, but to collect some family mementos and visit his family.

“I’m Here to Get an IBM 5100.”

John said his mission was to get a computer, specifically the IBM 5100 Portable Computer, introduced in 1975.

And he added one more line that felt like a wink to anyone who speaks Unix fluently: he referenced the Year 2038 problem. the real-world issue where some systems storing Unix time as a 32‑bit signed integer can’t represent dates past January 19, 2038.

So now the story had a spine: a real technical anxiety + a real machine + a motive that sounded like legacy support from hell.

Why the IBM 5100 Made Believers Lean Forward

The IBM 5100 was marketed as portable computer, back when “portable” meant 55 pounds. It had a built-in CRT, a keyboard, and tape storage. It looked like a suitcase with an 8-track tape and keyboard.

More importantly, it had a genuinely interesting architectural trick: through microcode, it could emulate aspects of other IBM systems and run languages like APL and BASIC in ways that were unusual for something that small at the time. In other words: it was a kind of digital Swiss Army Knife.

In truth, this was a pretty niche need when it was released, and within a couple decades you could emulate whatever you wanted on much more capable hardware. But this was 1975, 8 years before the first IBM PC.

So when “John Titor” built his time travel mission around this odd, heavy relic, and described it in a way that sounded like real technical familiarity, some readers didn’t hear “hoax.” The future needed this machine to stave off their Y2038 problem. OK, well maybe…I mean, NASA lost the Saturn V blueprints (they didn’t, but this is an old legend), so maybe future humanity lost something vital to fixing a future computer problem…?

Schematics and Insignias

As the posts continued, the story expanded:

- He described the time machine in technical-ish terms.

- He shared diagrams and photos.

- He talked about military markings and procedures.

- He explained “worldlines” and divergence – how timelines branch, how you can never return to the exact same version of your past.

Here’s a pic from this era:

This purports to be John sitting in his time-traveling machine, showing how the effects of gravity (or something) is bending a laser light.

You’ll notice a few things:

- It’s a 220px wide, because it’s the early Internet and that was high res back then.

- It’s grainy.

- It sounds like something a non-scientist might find plausible. Of course, time travel involves bizarre physics that bend laser light.

I remember when this photo made the rounds, and when I heard about it (on USENET), I was intrigued. Not intrigued enough to believe, but intrigued enough to see if there was any more info about it.

And there wasn’t. John posted it, but was cagey about details and the science involved. After all, he was just a soldier on a mission, not the engineer who built the time travel machine (which was a modified car…rather Back to the Future-esque). He was always dribbling out little tidbits, but he’d never sit down and answer someone’s question from end to end. You can read more about this alleged time travel machine on Wikipedia.

But whether the physics held up is almost beside the point. The story wasn’t persuasive because it was correct. It caught people’s attention because it seemed like maybe it could be plausible. A lot of it was John’s tone and the way he wrote. He was very low-key and just seemed to be chatting. He behaved exactly as you’d expect a friendly guy from the future to behave it he showed up and said “just stopping by, how’s life in this time?”

In 2025, we’re conditioned to reject everything we see online as either Photoshopped or AI-generated, but in the Titor era, the former was in its infancy and the latter didn’t exist.

The Predictions

Over time, Titor shared details on future history.

He described a grim America: political fracture, civil conflict, escalating violence, and ultimately global catastrophe. He was from Florida and had fought in the civil war as a member of an infantry unit called the Fighting Diamondbacks. Though in other posts, he seemed to indicate he’d avoided the war. If you were careful, you could see inconsistencies.

But here’s the crucial feature that made the story unusually resilient: he emphasized divergence. The idea that once he arrived, events wouldn’t unfold exactly the same way. That any “prediction” could fail because the timeline had shifted.

It’s the perfect narrative firewall.

If events match, believers point and say: See?

If events don’t match, believers shrug and say: Different worldline.

And Then…Silence

And finally, after months of posts and replies and arguments, the account stopped posting.

No confession. No credits. No final “it was all a prank.” No big announcement that “tomorrow I’m headed back to the future”.

Just absence.

Which is the cleanest ending a myth can ask for, because it leaves space for the audience to do what audiences always do: continue the story without you.

Afterlife

Over the years, John Titor became bigger than the forums:

- Posts were compiled, reposted, mirrored, turned into PDFs.

- Entire communities formed around analyzing and debating the material.

- A “John Titor Foundation” emerged in the early 2000s, adding an odd layer of legitimacy-by-presentation.

Who Was He?

Various investigations and theories have pointed toward real-world individuals connected to the “foundation” era, especially people with the right combination of technical knowledge and motivation. Those named have denied being “John Titor,” and there’s no universally accepted proof that settles it.

Later, multimedia artist Joseph Matheny (associated with early internet alternate-reality storytelling) has publicly claimed he consulted on the “project,” describing it as a deliberate experiment in modern folklore…though, again, claims about claims are part of why this story never truly ends.

So what’s the most honest conclusion?

John Titor is best understood as a highly effective early-internet legend: a character engineered (or evolved) to thrive in the an environment where a story can become stronger than its author.

But even if you land firmly in the skeptic camp, it’s hard not to admire the craftsmanship. Because in a world where time travel is supposed to be about destiny and drama, John Titor gave the internet something weirdly relatable:

- A soldier from the future, on a mission of pure operational necessity.

- A timeline-threatening apocalypse… and a very specific computer he needed to fix it.

- A prophecy wrapped in legacy support.

And for the kinds of people who still have a weird fondness for old hardware, old forums, and old internet mysteries, that is dangerously, irresistibly tantalizing.

Leave a Reply