MariaDB and PostgreSQL are the two leading SQL databases. Both adhere to many ANSI SQL standards, but these ANSI standards don’t specify all behaviors. The SQL statement themselves (such as SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE) are the areas where they have the most commonality. Where they differ the most is in their DDL (data definition language) commands, and the administrative/server components. In this tutorial, we’ll cover PostgreSQL.

MariaDB and PostgreSQL are the two leading SQL databases. Both adhere to many ANSI SQL standards, but these ANSI standards don’t specify all behaviors. The SQL statement themselves (such as SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE) are the areas where they have the most commonality. Where they differ the most is in their DDL (data definition language) commands, and the administrative/server components. In this tutorial, we’ll cover PostgreSQL.

History

PostgreSQL (sometimes called Postgres) is the successor to Ingres, which was a project at the University of California, Berkeley. Originally known simply as POSTGRES (a play on words), it was renamed to PostgreSQL in 1996.

Install

To install PostgreSQL on Debian systems:

apt-get install postgresql

On CentOS systems:

yum -y install postgresql-server

Post-Install Steps

On Debian, PostgreSQL comes ready to roll. On Centos, you need to initialize Pg with this command:

# /usr/bin/postgresql-setup --initdb * Initializing database in '/var/lib/pgsql/data' * Initialized, logs are in /var/lib/pgsql/initdb_postgresql.log

Configuration Files

On Debian systems, PostgreSQL configuration lives in /etc/postgresql/VERSION/main. So if you’re running version 11, the configuration files are in

/etc/postgresql/11/main

On Centos, PostgreSQL configuration files can be found in /var/lib/pgsql/data, regardless of version.

Starting and Stopping

PostgreSQL starts and starts like a normal systemd service:

systemctl start postgresql systemctl stop postgresql

Connecting

Typically you would connect this way from the command line:

psql -U someuser -W -h localhost somedb Password: psql (11.7 (Debian 11.7-0+deb10u1)) SSL connection (protocol: TLSv1.3, cipher: TLS_AES_256_GCM_SHA384, bits: 256, compression: off) Type "help" for help. somedb=>

The reason we use -h localhost is to force a network connection. Otherwise, peer authentication is used and PostgreSQL would expect your Unix username to be the same as your database username.

If connecting from an application, note that by default PostgreSQL runs on port 5432.

Super User Access

In PostgreSQL, the system ‘postgres’ account is the superuser.

# su - postgres $ psql psql (11.7 (Debian 11.7-0+deb10u1)) Type "help" for help. postgres=#

Scripted Access

If you are scripting PostgreSQL (perhaps for backups), you can eliminate the need to enter a password. There are two methods for accomplishing this. The first is to set the PGPASSWORD environment variable:

export PGPASSWORD=some-password

However, be advised that any user can see this environment variable in the process table. Hence, it’s better to use method two, which is to create a .pgpass file in the user’s home directory. It must be owned by that user and set to read/write by that user only:

# touch ~/.pgpass # chmod 600 ~/.pgpass

Then populate it with this format:

hostname:port:database:username:password

For example:

localhost:5432:somedb:user1:my-password

Then you could do this without a password:

psql -U user1 -h localhost somedb

Backing Up Databases

PostgreSQL can be backed up with the pg_dump program, which dumps your database to a .sql file that contains the SQL instructions for recreating the database. Basic usage for dumping a database called ‘mydb’ looks like this:

$ pg_dump mydb > /some/path/mydb.sql

To dump all databases:

pg_dumpall > /some/path/all.sql

Creating a New Database

$ psql psql (11.7 (Debian 11.7-0+deb10u1)) Type "help" for help. postgres=# create database new1; CREATE DATABASE postgres=#

You can also us the ‘createdb’ program in the shell:

$ createdb new2

Switching to a Database

Most PostgreSQL commands start with a backslash. For example, to switch databases, use \c (for “connect”):

$ psql psql (11.7 (Debian 11.7-0+deb10u1)) Type "help" for help. postgres=# \c new1; You are now connected to database "new1" as user "postgres". new1=#

Creating a User

new1=# create user someone with password 'something'; CREATE ROLE

To grant privileges on a database:

new1=# grant all privileges on database new1 to someone; GRANT

Note that this does not, as you might think, grant all privileges on all tables and sequences in that database. It only grants the ability to connect to that database and create objects. If you need to grant the ability to select, update, etc. existing tables, then you need to grant privileges on those tables individually. Alternatively, you can make the new user the owner of the database:

new1=# alter database new1 owner to someone; ALTER DATABASE

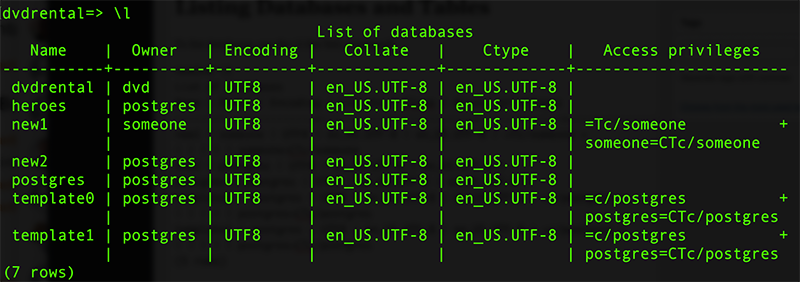

Listing Databases and Tables

To list databases, use the \l (for list) command:

To list tables, use \dt:

dvdrental=> \dt List of relations Schema | Name | Type | Owner --------+---------------+-------+---------- public | actor | table | postgres public | address | table | postgres public | category | table | postgres public | city | table | postgres public | country | table | postgres public | customer | table | postgres public | film | table | postgres public | film_actor | table | postgres public | film_category | table | postgres public | inventory | table | postgres public | language | table | postgres public | payment | table | postgres public | rental | table | postgres public | staff | table | postgres public | store | table | postgres (15 rows)

Creating Tables

Creating tables is a very standard SQL command. In this case, we are setting the ‘id’ column to be the primary key and also declaring it as type “serial”, which means that it will automatically increase with every insert.

CREATE TABLE superheroes ( id serial primary key, hero_name varchar(30), secret_identity varchar(30), team varchar(30) ); heroes=# CREATE TABLE superheroes ( heroes(# id serial primary key, heroes(# hero_name varchar(30), heroes(# secret_identity varchar(30), heroes(# team varchar(30) heroes(# ); CREATE TABLE heroes=#

Inserting Data

We'll add some rows, but we don't need to include the 'id' column in our insert statement because it will auto-increment for us. The "START TRANSACTION" is optional, as we'll explain next;

START TRANSACTION;

INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Iron Man', 'Tony Stark', 'Avengers');

INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Captain America', 'Steve Rogers', 'Avengers');

INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Thor', 'Donald Blake', 'Avengers');

INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('She-Hulk', 'Jennifer Walters', 'Avengers');

INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Wolverine', 'Logan', 'X-Men');

INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Cyclops', 'Scott Summers', 'X-Men');

INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Shadowcat', 'Kitty Pryde', 'X-Men');

INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Colossus', 'Piotr Rasputin', 'X-Men');

heroes=# START TRANSACTION;

START TRANSACTION

heroes=# INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Iron Man', 'Tony Stark', 'Avenger

s');

INSERT 0 1

heroes=# INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Captain America', 'Steve Rogers',

'Avengers');

INSERT 0 1

heroes=# INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Thor', 'Donald Blake', 'Avengers'

);

INSERT 0 1

heroes=# INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('She-Hulk', 'Jennifer Walters', 'A

vengers');

INSERT 0 1

heroes=# INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Wolverine', 'Logan', 'X-Men');

INSERT 0 1

heroes=# INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Cyclops', 'Scott Summers', 'X-Men

');

INSERT 0 1

heroes=# INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Shadowcat', 'Kitty Pryde', 'X-Men

');

INSERT 0 1

heroes=# INSERT INTO superheroes (hero_name, secret_identity, team) VALUES ('Colossus', 'Piotr Rasputin', 'X-M

en');

INSERT 0 1

heroes=#Transactions

We’re in the middle of a transaction thanks to the START TRANSACTION statement. From our perspective, this is what the superheroes table looks like:

heroes=# select count(*) from superheroes; count ------- 8 (1 row)

However, logging in from another session and running the same query produces this:

heroes=# select count(*) from superheroes; count ------- 0 (1 row)

This is because we haven’t committed the data yet. Let’s do so.

heroes=# commit; COMMIT heroes=#

Now both queries show:

heroes=# select count(*) from superheroes; count ------- 8 (1 row)

Let’s try one more transaction. I’m going to delete one of the heroes:

START TRANSACTION; DELETE FROM superheroes WHERE hero_name = 'Thor'; heroes=# START TRANSACTION; START TRANSACTION heroes=# DELETE FROM superheroes WHERE hero_name = 'Thor'; DELETE 1 heroes=#

heroes=# select count(*) from superheroes; count ------- 7 (1 row)

However, in the other session, I still see all rows:

heroes=# select count(*) from superheroes; count ------- 8 (1 row)

I could COMMIT in session #1, but I also have the option to ROLLBACK – in other words, abandon my changes. In this case, it’s only one statement, but I could have hundreds or thousands of statements pending commit. A COMMIT would apply them all, and a ROLLBACK would roll them all back. In this case, I’ll rollback:

heroes=# rollback; ROLLBACK heroes=# select count(*) from superheroes; count ------- 8 (1 row)

Querying Data

To query data, we use SELECT in the from “SELECT (columns) FROM (table)” and then optionally adding clauses to filter data (WHERE), group data (GROUP BY), and sort data (ORDER BY). Some examples:

heroes=# select secret_identity from superheroes where hero_name = 'Iron Man'; secret_identity ----------------- Tony Stark (1 row)

I can use “*” to mean all columns:

heroes=# select * from superheroes where hero_name = 'Thor'; id | hero_name | secret_identity | team ----+-----------+-----------------+---------- 3 | Thor | Donald Blake | Avengers (1 row)

Of course, I may have many rows:

heroes=# select hero_name, secret_identity from superheroes where team = 'Avengers' order by hero_name; hero_name | secret_identity -----------------+------------------ Captain America | Steve Rogers Iron Man | Tony Stark She-Hulk | Jennifer Walters Thor | Donald Blake (4 rows)

I can also use various database functions to summarize data:

heroes=# select team, count(*) from superheroes group by team order by team; team | count ----------+------- Avengers | 4 X-Men | 4 (2 rows)

Deleting Data

PostgreSQL uses a standard DELETE statement:

heroes=# delete from superheroes where team = 'X-Men'; DELETE 4

Updating Data

Perhaps She-Hulk decides to leave the Avengers (nerds: she joined in Avengers #221 and left in Avengers #243):

heroes=# update superheroes set team = NULL where hero_name = 'She-Hulk'; UPDATE 1 heroes=# select hero_name from superheroes where team = 'Avengers' order by hero_name; hero_name ----------------- Captain America Iron Man Thor (3 rows)

Learning More

– The official PostgreSQL page and documentation

– The “dvdrental” database, which is an unofficial but useful PostgreSQL test database

Leave a Reply